The ovaries are small but powerful organs that play a pivotal role in reproduction and hormone production. Located on either side of the uterus, they house thousands of follicles, each containing a potential egg. These follicles mature and release eggs during ovulation while also producing estrogen and progesterone, hormones indispensable for menstrual cycles and pregnancy. Comprehending their structure and function helps explain fertility, hormonal equilibrium, and common conditions like cysts or PCOS. There’s much more to uncover about how these tiny organs impact overall health.

Anatomy of the Ovaries

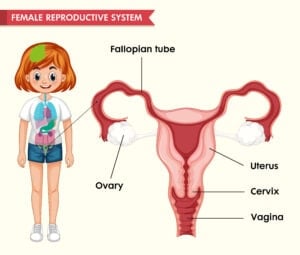

The ovaries are two small, oval-shaped organs nestled on either side of the uterus in the lower abdomen. As a key part of the female reproductive system, each ovary is surrounded by a thin layer called the germinal epithelium. Beneath this lies the ovarian cortex, where follicles containing immature eggs develop.

The inner part, called the medulla, houses blood vessels and nerves that keep the ovaries functioning. Ligaments connect them to the uterus and pelvic wall, ensuring stability. The ovaries play a pivotal role in hormone production and egg maturation, making them indispensable for fertility. Comprehending their anatomy helps in recognizing how they support reproductive health, ensuring clarity for those seeking knowledge about their body’s inner workings.

Location and Position of the Ovaries

Nestled within the pelvic cavity, the ovaries rest on either side of the uterus, secured in a shallow depression known as the ovarian fossa. Each ovary is located on either side of the uterus, anchored by the suspensory ligament, which connects it to the pelvic wall.

Measuring about 4 cm in length, the ovaries lie near the fallopian tubes, though they remain separate structures. Their position in the ovarian fossa provides stability while allowing slight movement. A layer of dense connective tissue, the tunica albuginea, surrounds each ovary, offering protection.

This strategic placement guarantees the ovaries remain accessible for egg release while maintaining their connection to reproductive pathways. Their proximity to the uterus and supporting ligaments underscores their role in fertility.

Structure and Layers of the Ovaries

The ovaries have a surface covered by the germinal epithelium, a layer of cuboidal or columnar cells that protect the embedded tissues.

Inside, the cortex contains developing ovarian follicles, while the medulla consists of loose connective tissue and blood vessels. These follicles house oocytes and their surrounding support cells, critical for reproductive function.

Surface Epithelium Characteristics

Covering the ovaries like a thin protective layer, the surface epithelium—also called the germinal epithelium—consists of simple cuboidal to columnar cells. This ovarian surface epithelium acts as a shield, safeguarding the underlying ovarian cortex where follicles develop.

Beneath the cortex lies the ovarian medulla, a region rich in blood vessels and nerves. The germinal epithelium is often mistaken as the source of egg cells, but its primary role is structural support. As the follicles mature in the cortex, the surface epithelium helps maintain the ovary’s shape and integrity.

Though delicate, it guarantees the ovary functions smoothly, allowing the follicles to grow and release eggs. Comprehending its role highlights how even small structures play crucial parts in reproductive health.

Cortex and Medulla Composition

Beneath the protective germinal epithelium lies the ovarian cortex, a dense region packed with developing follicles and supportive stroma. The ovarian cortex houses ovarian follicles at various stages of growth, embedded within the ovarian stroma—a network of connective tissue that provides structural support and nutrients. This outer layer is key for follicle development, with the stroma ensuring proper hormone delivery and tissue integrity.

Deeper within the ovary, the ovarian medulla consists of looser connective tissue, blood vessels, and nerves entering through the hilum. Unlike the cortex, the medulla focuses on supplying oxygen and nutrients rather than follicle maturation. Together, these layers create a dynamic environment, balancing reproductive function with essential blood flow and neural connections.

Ovarian Follicle Structure

Since the ovarian cortex provides the environment for follicle development, comprehending the layers of an ovarian follicle helps explain how eggs mature and prepare for ovulation. Each ovarian follicle houses an oocyte, the immature egg, surrounded by protective layers. The zona pellucida, a gel-like shell, encases the oocyte, while the corona radiata—a ring of granulosa cells—nourishes it.

The membrana granulosa, a thicker layer, produces estrogen, supporting follicle growth. Outside this, theca cells form a supportive framework, secreting androgens converted to estrogen. As the follicle matures, fluid accumulates, forming the antrum, a key marker of readiness for ovulation. The cumulus oophorus, a cluster of granulosa cells, anchors the oocyte until release. Examining these layers clarifies how follicles nurture and release eggs, essential for fertility.

Ovarian Ligaments and Attachments

The ovaries are held in place by a network of ligaments that provide stability and support within the pelvic cavity.

The ovarian ligament connects the ovary to the uterus, while the suspensory ligament anchors it to the pelvic wall. The broad ligament, including the mesovarium, further secures the ovary and its associated structures.

Ligament Support System

Although the ovaries are small, their position in the body is held firmly by several supportive ligaments. The suspensory ligament of the ovary anchors each ovary to the pelvic wall, providing stability.

The ovarian ligament connects the ovary to the uterus, while the broad ligament—a fold of peritoneum—encases these structures. Within the broad ligament lies the mesovarium, which directly covers the ovary.

The ovarian pedicle, a bundle of tissues, includes the fallopian tube, mesovarium, ovarian ligament, and blood vessels. These ligaments guarantee, ensure, and secure the ovaries remain securely positioned within the peritoneal cavity, despite not being fully enclosed by peritoneum. This support system allows for proper function while maintaining flexibility.

Ovarian Suspensory Function

Holding the ovaries securely in place, a network of ligaments works like natural anchors to keep these essential organs stable yet flexible. The suspensory ligament connects each ovary to the pelvic wall, providing support while housing vital blood vessels that supply oxygen and nutrients.

This ligament guarantees the ovary remains positioned near the fallopian tube, allowing released eggs to travel smoothly. The ovarian ligament, a separate structure, tethers the ovary to the uterus, adding stability without restricting movement. Together, these ligaments balance mobility and security, adapting to changes during ovulation or pregnancy.

Blood vessels within the suspensory ligament maintain circulation, keeping the ovary healthy. This delicate arrangement ensures the ovaries function efficiently while staying protected within the pelvic cavity.

Broad Ligament Connections

Beyond their stabilizing ligaments, broad ligament connections further secure the ovaries in place. The ovarian ligament anchors each ovary to the uterus, while the suspensory ligament tethers it to the pelvic wall, verifying stability.

The mesovarium, a fold of the broad ligament, wraps around the ovary, connecting it to surrounding structures. This arrangement forms part of the ovarian pedicle, which includes blood vessels and the fallopian tube, supplying nutrients and support.

Though the ovaries lie uncovered in the peritoneal cavity, these attachments prevent excessive movement. Comprehending these connections helps explain how the ovaries remain positioned for ideal function. Their precise placement guarantees reproductive health, highlighting the importance of each ligament’s role in maintaining stability and proper blood flow.

Blood Supply and Innervation of the Ovaries

How do the ovaries stay nourished and connected to the body’s systems? The arterial blood supply to the ovaries comes primarily from the ovarian arteries, branching directly from the abdominal aorta. These vessels deliver oxygen and nutrients essential for hormone production and egg development.

Blood exits through the ovarian veins, with the left draining into the renal vein and the right into the inferior vena cava. Nerves reach the ovaries via the suspensory ligament, providing both sympathetic and parasympathetic signals that regulate function. This intricate network guarantees the ovaries can perform their reproductive and hormonal roles effectively.

Proper blood supply and nerve signaling are critical—without them, ovulation and hormone balance could be disrupted. The lymphatic drainage, though not discussed here, also plays a supporting role in maintaining ovarian health.

Lymphatic Drainage of the Ovaries

The lymphatic vessels from the ovaries primarily follow pathways along the broad ligament, eventually draining into the para-aortic lymph nodes.

These major lymph node groups also include connections to the external iliac, internal iliac, and sacral nodes, which can receive ovarian lymphatic flow. Comprehending this drainage pattern is clinically significant, especially in evaluating the spread of ovarian cancer and planning appropriate treatments.

Lymphatic Vessel Pathways

Like tiny highways for immune cells, lymphatic vessels from the ovaries follow specific pathways to drain fluid and filter waste. These vessels play a vital role in maintaining ovarian health by removing excess lymph and waste products.

- Primary Routes: Lymphatic drainage from the ovaries primarily flows to the para-aortic lymph nodes, located near the aorta.

- Secondary Pathways: Some lymph also drains into the pelvic and hypogastric lymph nodes, ensuring thorough waste removal.

- Ligament Travel: Lymphatic vessels run alongside the ovarian ligament and suspensory ligament, acting as natural drainage channels.

- Cancer Spread: In ovarian cancer, these pathways can unfortunately allow malignant cells to reach lymph nodes, affecting treatment effects.

Understanding these pathways helps in diagnosing and managing ovarian conditions, emphasizing the importance of lymphatic health in overall reproductive function.

Major Lymph Node Groups

Where does lymph from the ovaries go? The lymphatic drainage of the ovaries primarily follows the ovarian blood vessels, carrying lymph to the paraaortic lymph nodes near the aorta. Some lymph may also reach the external iliac, obturator, or inguinal lymph nodes.

These lymph nodes act as filters, trapping harmful substances or metastatic ovarian cancer cells that spread through the lymphatic system. The paraaortic nodes are the most common site for initial lymphatic spread, making them essential in cancer staging. Comprehension of this drainage pattern helps explain how ovarian cancer progresses and why lymph node involvement affects treatment decisions.

The lymphatic and blood pathways work together, but the lymph nodes serve as key checkpoints for detecting disease spread, emphasizing their role in ovarian health.

Clinical Significance of Drainage

Comprehending lymphatic drainage helps elucidate why ovarian cancer frequently disseminates initially to the para-aortic lymph nodes. The lymphatic system acts as a pathway for cancer cells, making lymph node involvement pivotal in staging and treatment.

The ovaries drain to the para-aortic lymph nodes, with secondary pathways to the external iliac and obturator nodes.

Ovarian cancer often metastasizes through these lymphatic channels, making timely detection imperative.

Lymph node involvement indicates disease progression, influencing treatment decisions.

Techniques like sentinel lymph node biopsy help identify affected nodes, improving surgical accuracy.

Understanding these pathways guarantees better management of ovarian cancer, emphasizing the need for targeted therapies and prompt intervention. The lymphatic system’s role underscores why monitoring lymph nodes is indispensable in patient care.

Ovarian Function in Gamete Production

The ovaries play a critical role in female reproduction by producing and releasing eggs, a process indispensable for fertility. These organs house germ cells, which develop into female gametes, or eggs, through a carefully regulated cycle.

Each menstrual cycle, the ovaries produce eggs, with typically one mature egg released for potential fertilization. This egg develops within a follicle, a small sac in the ovarian cortex, before being released during ovulation. The process guarantees that only the healthiest egg is selected, maximizing the chance of successful conception.

While millions of follicles exist at birth, only a fraction will ever mature. Comprehending this function helps explain how the ovaries support reproductive health, emphasizing their essential role in creating life. Proper ovarian function is key to fertility and overall well-being.

Hormones Produced by the Ovaries

Beyond their role in egg production, the ovaries also act as hormone factories, releasing substances that influence everything from reproductive health to physical development. These hormones regulate key processes in the body and maintain overall well-being.

Estrogen: Drives the development of female secondary sexual characteristics (like breast growth) and prepares the uterus for potential pregnancy during the menstrual cycle.

Progesterone: Secreted by the corpus luteum after ovulation, it supports the uterine lining to nurture a fertilized egg.

Inhibin: Signals the pituitary gland to reduce follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) production, helping control egg maturation.

Testosterone: Though produced in small amounts, it contributes to libido, muscle strength, and secondary sexual traits in women.

Together, these hormones secure reproductive function and influence broader health.

Common Ovarian Conditions and Disorders

Ovarian conditions and disorders range from temporary cysts to serious health threats, impacting women in different ways. Ovarian cysts, fluid-filled sacs on or within the ovaries, are often harmless but can cause pain if they rupture.

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) disrupts hormone balance, leading to irregular periods and cysts. Ovarian cancer, though less prevalent, is dangerous due to subtle preliminary symptoms like bloating or pelvic discomfort. Ovarian torsion, a sudden twist of the ovary, requires urgent care to prevent tissue damage.

Premature ovarian failure, where ovaries stop functioning before age 40, triggers premature menopause and fertility challenges. While some conditions resolve naturally, others need medical attention. Regular check-ups help detect issues promptly, ensuring better results and peace of mind.

Clinical Significance of Ovarian Health

How crucial is ovarian health in a woman’s overall well-being? The ovaries play a pivotal role in reproductive and systemic health, influencing fertility, hormone balance, and long-term wellness. If ovarian function is compromised, it can lead to significant health challenges.

Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) disrupts hormone levels, often causing irregular periods and affecting fertility.

Ovarian torsion is a rare but urgent condition where the ovary twists, cutting off blood flow and requiring immediate care.

Premature ovarian failure halts normal function before age 40, leading to early menopause and infertility.

Ovarian cysts, though usually harmless, may cause pain or complications if they rupture or grow too large.

Maintaining ovarian health through regular check-ups and timely intervention can safeguard fertility and overall well-being. Emerging techniques like ovarian tissue cryopreservation offer hope for preserving reproductive potential.

Conclusion

The ovaries, like tiny powerhouses, keep the body’s rhythm in harmony. Consider Sarah, who struggled with irregular periods until her doctor explained how ovarian hormones orchestrate her cycle. Just as a conductor guides an orchestra, these organs balance fertility and health. Comprehension of their structure and function isn’t just science—it’s the key to recognizing whenever something’s off and taking charge of well-being, one follicle at a time.