Testicle anatomy examines the structure and role of the testes in the male reproductive system. This article explains their positioning, external and internal features, and blood supply, giving you a thorough understanding of their function.

Key Takeaways

The testes play a crucial role in male reproduction, producing sperm and hormones while needing a cooler environment for optimal function.

Hormonal regulation is vital for testicular function, with testosterone, FSH, and LH working together to ensure sperm production and overall male health.

Testicular disorders, like torsion and hydrocele, highlight the importance of recognizing symptoms early for effective treatment and maintaining reproductive health.

Anatomical Position and Structure

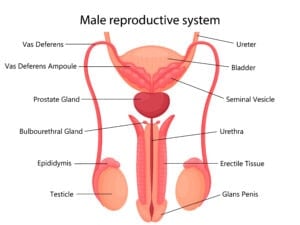

The testes, located in the scrotum, are the cornerstone of the male reproductive system, playing a vital role in producing sperm cells and male hormones. During embryonic development, the testes descend through the inguinal canal to their position in the scrotum. This relocation allows the testes to reside in a cooler environment than the body’s core temperature, optimizing sperm production.

Each testis is ellipsoid in shape and measures approximately 3 cm by 5 cm in length and 2 cm to 3 cm in width. Suspended by the spermatic cord and attached to the scrotum by the scrotal ligament, the testes are enveloped by the tunica vaginalis, a double-layered structure that provides protection and support.

Interestingly, the left testis is typically positioned slightly lower than the right, a common trait among males. This positioning is fundamental to the testicles’ function and overall male reproductive health.

External Anatomy of the Testicle

The external anatomy of the testicle includes structures crucial for reproductive health: the scrotum, epididymis, and spermatic cord, each playing a unique role in housing, protecting, and maturing sperm cells.

1. Scrotum

The scrotum is a protective pouch that holds the testicles and regulates temperature. It contains smooth muscle fibers that contract or relax, adjusting its position in response to temperature changes. This mechanism maintains the testes at an optimal temperature for sperm production, slightly cooler than the body.

The scrotum’s temperature regulation is crucial for healthy sperm production and overall male reproductive health.

2. Epididymis

The epididymis, located on the surface of the testicle, is essential for sperm maturation and storage. This long, coiled tube, approximately 6 to 7 meters when uncoiled, provides ample space for sperm to mature and become motile. It is divided into three sections: the head, body, and tail, each playing distinct roles in sperm processing.

In the head of the epididymis, sperm cells begin their maturation. As they move through the body and tail, they mature further, becoming capable of fertilizing an egg. The epididymis stores mature sperm and prepares them for ejaculation, making it a critical component of the male reproductive system.

3. Spermatic Cord

The spermatic cord connects the testicle to the body, encompassing blood vessels, nerves, and the vas deferens. It provides a pathway for the testicular artery and vein, ensuring blood supply and drainage to the testicles. These blood vessels deliver oxygen and nutrients to the testes, ensuring their proper function.

The spermatic cord also contains nerves that provide sensory and autonomic innervation to the testes. The vas deferens, a muscular tube within the cord, transports mature sperm from the epididymis to the urethra during ejaculation. This complex structure is crucial for the overall function and health of the male reproductive system.

Internal Anatomy of the Testicle

The internal anatomy of the testicle reveals structures essential for reproductive function. Each testicle is divided into lobules containing tightly coiled seminiferous tubules, where sperm cells are produced.

Additionally, the interstitial tissue houses Leydig cells responsible for hormone production.

1. Seminiferous Tubules

Seminiferous tubules are where sperm cells develop through spermatogenesis. Each testicle contains approximately 800 seminiferous tubules, providing a vast area for sperm production. These tubules are lined with germ cells that undergo several stages of division and maturation to produce mature spermatozoa, including the seminiferous tubule.

The seminiferous tubules are not only the birthplace of sperm but also play a crucial role in their early development. Sertoli cells within the tubules provide nutritional support and create an optimal environment for developing sperm, ensuring the continuous production of healthy sperm cells, vital for male fertility.

2. Leydig Cells

Located in the connective tissue between the seminiferous tubules, Leydig cells produce testosterone. This hormone is essential for developing male reproductive tissues and promoting secondary sexual characteristics. Leydig cells play a pivotal role in maintaining male reproductive health by synthesizing and secreting testosterone.

3. Sertoli Cells

Sertoli cells, found within the seminiferous tubules, support developing sperm cells by supplying nutrients and creating a conducive environment for maturation. Additionally, Sertoli cells form the blood-testis barrier, protecting developing sperm from harmful substances and immune responses.

This dual role underscores their importance in spermatogenesis.

Hormonal Regulation of Testicular Function

Hormonal regulation is crucial for male fertility, as hormones control sperm production and maturation. Disruptions in hormonal balance can lead to reproductive disorders, highlighting the importance of understanding the role of hormones in testicular function.

1. Testosterone Production

Testosterone, produced mainly by Leydig cells in the testes, is vital for male sexual development and function. It regulates the development of male reproductive tissues and secondary sexual characteristics.

The hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis controls testosterone levels, ensuring balanced production for overall male health.

2. Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH) and Luteinizing Hormone (LH)

FSH and LH, secreted by the anterior pituitary gland, stimulate sperm production and testosterone secretion. FSH supports sperm cell development, while LH stimulates testosterone production from Leydig cells.

These hormones work together to maintain proper testicular function and male fertility.

3. Inhibin

Inhibin, produced by Sertoli cells, provides feedback regulation to lower FSH production, thereby controlling spermatogenesis. This hormone ensures that sperm production remains within optimal levels, preventing overproduction and maintaining hormonal balance.

Common Testicular Disorders and Conditions

Testicular health can be compromised by various disorders and conditions, each with unique symptoms and treatment approaches. Understanding these issues is essential for early detection and effective management.

1. Testicular Torsion

Testicular torsion occurs when a testicle twists on its spermatic cord, restricting blood flow and causing severe pain and swelling. This condition is most frequently observed in males aged 12 to 18 but can occur at any age. Immediate medical intervention is needed to prevent tissue loss and potential infertility.

Symptoms of testicular torsion include sudden severe pain in the scrotum, swelling, and nausea. Treatment typically involves surgical correction to untwist the spermatic cord and secure the testicle, preventing recurrence.

Early recognition and prompt medical attention can save the affected testicle and preserve fertility.

2. Hydrocele

A hydrocele is characterized by fluid accumulation around one or both testicles, causing scrotal swelling. Most hydroceles do not require treatment and may resolve on their own.

However, if the swelling causes discomfort or does not resolve, surgery may be necessary to drain the fluid and alleviate symptoms.

3. Varicocele

Varicocele involves swelling of veins within the spermatic cord, which can reduce fertility by raising testicular temperature. Common symptoms include a dull ache in the scrotum and visible enlarged veins.

Surgical options, such as varicocelectomy, may be considered if varicocele leads to pain or infertility.

4. Orchitis

Orchitis is an inflammation of the testicles, often caused by viral or bacterial infections. It can lead to pain and swelling, significantly impacting testicular function.

Management typically involves treating the underlying infection and alleviating symptoms with medications like NSAIDs.

Testicle Health and Maintenance

Maintaining testicular health is crucial for reproductive function and overall well-being. Regular self-examinations, proper protection during physical activities, and a healthy lifestyle significantly impact testicular health.

1. Regular Self-Examination

Performing a monthly self-exam starting at age 15 helps recognize changes that may indicate health issues. Gently roll each testicle between your fingers, feeling for any lumps, swelling, or changes in size or consistency.

Early detection of abnormalities can lead to prompt medical intervention and better outcomes.

2. Proper Protection and Safety

Protecting the testicles during physical activities is essential to avoid injuries. Wearing protective gear, such as athletic cups, during sports or high-impact activities can significantly reduce the risk of testicular trauma.

Avoiding unnecessary risks and ensuring proper safety measures can help maintain testicular health and prevent complications.

3. Impact of Lifestyle on Testicle Health

A healthy lifestyle, including a balanced diet and regular physical activity, contributes positively to testicular function. Diets rich in antioxidants can enhance sperm production and overall testicular health.

Limiting exposure to harmful chemicals and environmental toxins also supports testicular health, reducing the risk of disorders.

Blood Supply and Venous Drainage

The blood supply to the testes is primarily provided by the paired testicular arteries, which originate from the abdominal aorta. These arteries ensure that the testicles receive oxygen-rich blood, crucial for their function. The right testicular vein drains directly into the inferior vena cava, while the left testicular vein drains into the left renal vein. This venous drainage system is facilitated by the pampiniform plexus, a network of veins that helps regulate the temperature of the blood entering the testes.

The testicular plexus, formed by fibers from the aortic plexus, associates with the testicular arteries, contributing to the regulation of blood flow and hormonal signaling. Proper blood supply and venous drainage are essential for maintaining the health and function of the testes.

Lymphatic System

The lymphatic drainage of the testes involves pathways that include the lumbar and para-aortic nodes. Lymph from the testes primarily drains into the preaortic lymph nodes, located near the abdominal aorta.

Additionally, the para-aortic lymph nodes receive lymph drainage from the testes, playing a crucial role in the immune response and fluid balance within the testicular environment.

Nerve Supply

The testes are innervated by autonomic nerves, which include both sympathetic and parasympathetic fibers. Sympathetic nerve fibers originate from spinal cord segments T10 to T11, while parasympathetic fibers primarily derive from the vagus nerve. This nerve supply is essential for regulating blood flow, sensation, and the overall function of the testicles, ensuring they respond appropriately to physiological demands.

Embryological Development

During early embryological development, the testes begin as undifferentiated gonads, with the SRY gene playing a pivotal role in their differentiation into testes. As the fetus matures, the testes start producing testosterone, which is crucial for male sexual differentiation and the development of external genitalia.

The descent of the testes involves two stages: the transabdominal phase and the inguinoscrotal phase. The gubernaculum, a structure that elongates and anchors the testes to the inguinal region, facilitates their descent through traction. The processus vaginalis forms as the gubernaculum elongates, creating a pathway for the testes to descend into the scrotum.

Leydig insulin-like hormone (Insl3) plays a significant role in the transabdominal stage of testicular descent, ensuring the proper positioning of the testes.

Coverings and Support Structures

The testes are encapsulated by the tunica albuginea, a tough fibrous layer that extends inward to form septa, dividing the testes into lobules. The tunica vaginalis, consisting of a visceral layer that directly covers the testis and a parietal layer lining the scrotal sac, provides additional protection.

The cremaster muscle, derived from the internal oblique muscle, helps regulate the temperature of the testes by raising or lowering them in response to temperature changes.

The Epididymis and Duct System

The epididymis is responsible for maturing sperm and preparing them for eventual fertilization. It also serves as storage for sperm, ensuring they are kept in optimal conditions until ejaculation.

The ductus deferens, a muscular tube that varies in length from approximately 30 to 45 centimeters, transports mature sperm from the epididymis to the urethra. During ejaculation, contractions help move sperm from the epididymis into the ductus deferens, which connects to the urethra.

This duct system is crucial for the transport and storage of sperm, ensuring that mature sperm cells are available for fertilization when needed.

Clinical Conditions and Variants

Various clinical conditions and variants can affect the testicles, including cryptorchidism, hydrocele, and polyorchidism. Cryptorchidism, or undescended testes, affects 1.8% to 8.4% of newborn boys and increases the risk of testicular cancer if not treated.

Hydrocele, characterized by the accumulation of serous fluid between the layers of the tunica vaginalis, can develop from complications like communicating hydrocele and inguinal hernia. Polyorchidism, though rare, involves the presence of supernumerary testes and is often discovered incidentally during other examinations.

Surgical Considerations

Surgical intervention is often required for conditions like testicular torsion and undescended testicles. The absence of the cremasteric reflex is a common sign associated with testicular torsion, necessitating immediate surgical correction to prevent potential loss of the testicle.

Inguinal hernias, commonly associated with undescended testicles, may also require surgical repair concurrently. Fixing the testes in the scrotum during surgery helps prevent recurrence and ensures proper testicular function.