The autistic stare often puzzles those unfamiliar with autism, but it holds deeper meaning for individuals on the spectrum. Unlike neurotypical eye contact, which feels natural to most, prolonged or distant gazes in autism stem from sensory differences and neurological wiring. Some find direct eye contact overwhelming, while others use it to focus better on conversations. Misinterpretations can lead to social friction, but appreciating this behavior fosters empathy. Comprehending the reasons behind the stare helps bridge communication gaps.

Defining the Autistic Stare

Though eye contact can feel natural for many, individuals with autism often experience it differently, sometimes exhibiting what’s referred to as the “autistic stare.” This gaze, which could seem intense, distant, or unfocused to others, isn’t about rudeness or disinterest but rather reflects differences in sensory processing and social communication.

For those with autism spectrum disorder, eye contact can feel overwhelming or distracting, leading to unique communication styles that prioritize comfort over social expectations. The autistic stare may involve prolonged focus on a person’s face without typical back-and-forth engagement, or it might appear as if the individual is looking through someone.

Comprehension of the autistic point of view helps recognize that this behavior isn’t intentional but part of how some navigate social interactions differently.

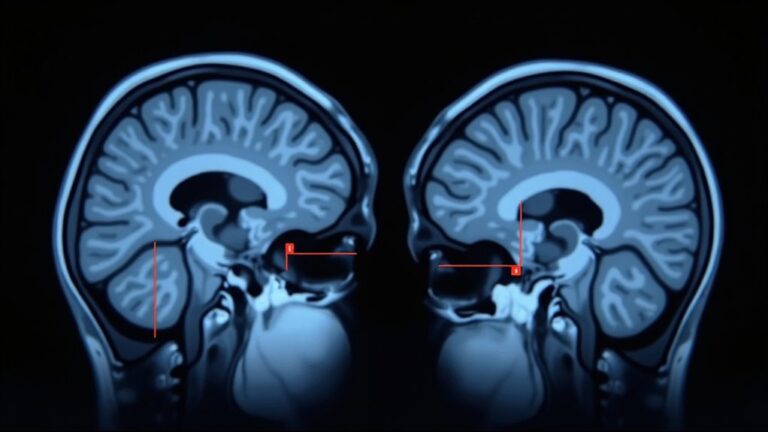

Neurological Perspectives on the Autistic Gaze

Research into the autistic gaze reveals neurological differences that shape how individuals on the spectrum process eye contact. Unlike neurotypical individuals, who often rely on eye contact for social interactions, autistic people may find direct gaze overwhelming or distracting due to unique visual processing patterns.

These differences can affect communication strategies, making traditional expectations challenging. For some, evading eye contact helps focus on verbal content rather than nonverbal cues. ABA Therapy sometimes addresses these behaviors by teaching alternative ways to engage, though preferences vary widely.

Comprehending these neurological perspectives fosters empathy, as the autistic gaze isn’t a lack of interest but a different way of experiencing the world. Acknowledging this helps create more inclusive environments where communication feels natural for everyone.

Sensory Processing and Eye Contact Differences

Because sensory processing shapes how autistic individuals experience eye contact, many find direct gaze uncomfortable or even painful. Sensory processing issues can make the intensity of another person’s eyes overwhelming, leading to challenges faced by individuals when making eye contact.

For some, the visual input feels too bright or sharp, while others struggle with difficulties in comprehending the social cues tied to gaze. This doesn’t mean disinterest—autistic individuals may listen intently while looking away to reduce sensory overload. The brain prioritizes comfort, so avoiding eye contact helps manage stimuli.

Acknowledging these differences fosters empathy, perceiving that unconventional gaze patterns stem from neurological wiring, not rudeness. Adjusting expectations allows for smoother interactions, respecting each person’s unique sensory needs.

Common Misinterpretations of the Autistic Stare

The autistic stare is often misinterpreted as disinterest, leaving others feeling ignored or unimportant.

Some perceive it as rudeness, assuming the person is intentionally avoiding engagement. These misunderstandings stem from a lack of awareness about how autism affects eye contact and social cues.

Misread as Disinterest

Many people assume a blank or intense stare from someone with autism means they’re bored or rude. This misconception stems from neurotypical expectations about social communication, where eye contact signals engagement.

For autistic individuals, sensory sensitivities often make direct eye contact overwhelming or distracting, leading to avoidance or prolonged staring. Sensory overload or difficulties can cause them to focus inward, processing information differently.

The implications of the autistic stare being misread include strained interactions and unfair judgments. Rather than disinterest, it may reflect deep concentration or a need to regulate input.

Comprehension of the role of sensory sensitivities helps reframe these moments as part of unique communication styles, not indifference. Educating others reduces stigma and fosters more inclusive connections.

Seen as Rudeness

As neurotypical individuals encounter an intense or distant gaze from someone with autism, they could perceive it personally, interpreting it as detachment or lack of respect. This misunderstanding stems from differences in how people with autism process social cues.

While neurotypical individuals rely heavily on eye contact to gauge involvement, those with autism may avoid it due to sensory overload or difficulty interpreting nonverbal cues. Their stare isn’t meant to signal disinterest or rudeness—it’s simply their way of managing overwhelming stimuli.

Without this awareness, others might assume the person isn’t trying to engage, when in reality, they’re navigating social interactions differently. Acknowledging these nuances helps bridge communication gaps and fosters more inclusive interactions.

Social Communication Challenges Related to Staring

As someone with autism holds eye contact for longer than customary, it may generate bewilderment or unease in social settings. This difference in communication can lead to misunderstandings, as neurotypical individuals often interpret prolonged staring as intense or invasive.

For autistic individuals, maintaining eye contact might feel overwhelming or distracting, while avoiding it entirely can seem disengaged. These challenges highlight the importance of comprehending the experiences of those with autism, as their social skills operate differently.

In social situations, what appears as a “stare” could simply be an attempt to focus or process information. Identifying these differences in communication fosters empathy and reduces discomfort for both parties. By acknowledging these nuances, people can create more inclusive interactions that respect diverse ways of connecting.

Comparing Autistic and Neurotypical Eye Contact

Eye contact works differently for autistic and neurotypical individuals, creating distinct social experiences. For neurotypical people, eye contact and facial expressions often feel natural, helping them connect and communicate.

However, individuals on the autism spectrum may find it uncomfortable or overwhelming to maintain eye contact, not because they lack interest but due to sensory or processing differences. These contrasting experiences of individuals can lead to misunderstandings, where avoiding gaze is misinterpreted as disengagement.

The social implications are significant, as neurotypical norms often prioritize eye contact as a sign of attention or respect. Acknowledging these differences fosters empathy, allowing for more inclusive interactions. Appreciating that autistic staring or gaze avoidance isn’t intentional but part of unique neurology helps bridge communication gaps.

The Role of Sensory Overload in Staring Behaviors

Sensory overload often makes eye contact overwhelming for autistic individuals, leading to the autistic stare as a way to cope. Bright lights, loud noises, or too much social stimulation can make focusing on faces feel impossible.

This behavior helps them manage sensory input while still being present in interactions.

Sensory Input Overwhelm

For many autistic individuals, the world can feel like a flood of overwhelming sensations—bright lights, loud sounds, or even the texture of clothing. Sensory overwhelm often triggers the autistic stare, a coping mechanism to manage sensory overload. This behavior helps them self-regulate by reducing sensory input, allowing their nervous system to reset.

Key reasons the autistic stare occurs during sensory overload include:

- Sensory sensitivities: Heightened perceptions make everyday stimuli intolerable.

- Neurological differences: The brain processes sensory input unusually, increasing overwhelm.

- Avoidance: Staring minimizes engagement with distressing environments.

- Self-protection: It creates a mental buffer against sensory assault.

The stare isn’t disinterest but a survival strategy. Comprehension of this fosters empathy for autistic individuals traversing a world not designed for their sensory needs.

Eye Contact Difficulties

Many autistic individuals find direct eye contact uncomfortable, even painful, because their brains process social cues differently. The intensity of contact and facial expressions during conversations can trigger sensory overload, making sustained eye contact exhausting.

This reaction isn’t a choice but a neurological response, where the brain struggles to filter overwhelming stimuli. As a result, autistic individuals may evade gaze or adopt a distant stare to self-regulate.

These behaviors present unique challenges in social settings, where lack of eye contact is often perceived as disinterest. By recognizing these sensory differences, others can gain a better comprehension of autistic communication styles.

Instead of forcing eye contact, offering patience and alternative ways to engage fosters more meaningful connections without added stress. The key lies in empathy, not expectation.

Strategies for Supporting Individuals With the Autistic Stare

Supporting individuals who use the autistic stare begins with comprehension of its purpose—whether it’s a way to manage sensory input, focus, or social discomfort. Creating a supportive environment reduces sensory overload, making interactions less overwhelming.

Family members and caregivers can foster effective communication through respecting the individual’s need for the stare while gently introducing alternatives.

Key strategies include:

- Adjusting the environment—dim lights or quiet spaces help minimize sensory challenges.

- Using visual aids—pictures or written cues reduce pressure to maintain eye contact.

- Educating others—sharing perspectives helps avoid misunderstandings about the stare’s meaning.

- Practicing social skills—gradual exposure to eye contact builds comfort without forcing it.

Personal Experiences and Insights on the Autistic Stare

People who use the autistic stare often share how it helps them navigate overwhelming situations, offering a sense of control in a world that doesn’t always make sense to them. Their unique experiences reveal valuable insights into the comprehension of autism, showing how the stare serves as a coping mechanism in daily life. For some, it’s a way to block out uncomfortable sensory input, while others use it to focus amidst chaos.

| Situation | Purpose of the Stare |

|---|---|

| Overwhelming crowds | Reduces sensory overload |

| Complex social interactions | Creates mental space |

| Unfamiliar environments | Provides emotional grounding |

These perspectives highlight how the stare isn’t just a behavior—it’s a tool for managing discomfort and finding stability.

Conclusion

The autism stare carries more weight than a thousand unspoken words, revealing an entire universe of sensory experience beyond what neurotypical eyes can perceive. Far from mere blankness, this gaze represents a deliberate strategy for traversing overwhelming environments – like wearing noise-canceling headphones for the soul’s overloaded circuits. As soon as approached with patience rather than criticism, what initially seems like detachment often transforms into profound connection on entirely different neurological terms.